Scripting

Introduction, Motivation

Game Engines are often written with performance in mind. One effect of prioritizing performance is that we choose highly performant languages such as C++ or even Assembler for implementing the game engine. While allowing us to make optimal use of our hardware platform and managing performance-critical aspects ourselves, we loose some other advantages. For example, not everyone knows C++ or Assembler, certainly not at the level needed to code core game functions. However, more people might know how to program in a scripting language such as Javascript or Python.

These scripting languages have some properties that they share. They are often interpreted, meaning that they are not compiled and linked but instead they are interpreted at runtime. Often, they are not statically typed but we have dynamic typing.

The following is a list of positive properties that scripting languages can have in game development:

- Designer-friendly By choosing a language that is easy to learn, we allow designers, artists and everyone else who is not a core programmer to change the behavior of objects in the game. For example, a scripting language can allow artists to add functional objects (e.g. a box that can be opened by the player) with working behaviors instead of forcing them to submit “raw” assets and then asking a programmer to add functionality. Another example is a designer who can fine-tune balancing properties by herself while testing the game.

- Easy to learn Since many scripting languages are designed to be easy to learn (e.g. by omitting aspects of low-level languages such as memory management or pointers), new team members can be brought up to speed quickly.

- Adaptable Languages such as LUA or Ruby allow programmers to work on the language itself to a certain extent. This allows the language to be changed for the purpose at hand to a certain degree. This leads to the languages becoming domain-specific languages (DSL) which are fine-tuned for a certain purpose.

- Concurrency Many scripting languages have the concept of coroutines. This means that, instead of returning only once, the function can break execution at any point and resume at a later point. Think for example of a function that is intended to update a value after waiting for 5 seconds. In the normal model of a game engine, you would maybe resort to something like a state machine with a state “waiting for 5 seconds”. This would break the readability of this really simple function, as it spreads the code out over several functions. A coroutine, on the other hand, would be able to yield execution to other coroutines while it was waiting and continue work after the 5 seconds have passed.

- No compilation Since many scripting languages are interpreted, the scripts have no compilation time. For large projects which might take hours to compile, this means that gameplay code can be changed pretty much instantly without incurring any recompilation costs. Furthermore, this allows exchanging functions during runtime easily. Another advantage of an interpreter is that you can add a command line to your game engine for entering scripting language commands, making it simple to get debug information for your game.

- Mod support This topic is closely related to the previous one, but is important enough to warrant a new bullet. Using a scripting language, you can expose parts of your game logic to the players, allowing them to change parts of the game or even add new functionality. The core parts are compile for C++ or another language, while the high-level code is provided in the scripting language, so modders can learn from them and create their own additions to the game. This increases the shelf life and long-term sales of a game.

Examples

The first uses of scripting languages can be traced back to the adventure game genre and the associated interactive fiction. That this genre first required the use of scripting languages for describing the gameplay makes sense: In a story-based adventure game, the gameplay consists mainly out of the player trying one of a set of actions on the world, and the game engine reacting with a scripted response, either graphically or as text. This means that we find two aspects: one is getting the game running in the first place, handling inputs and displaying graphics and animations. The other aspect is the one driving the former: the scripts which govern the responses of the game to the player’s actions. Infocom, famous for interactive fiction such as Zork, and both of the two dominating companies during the dawn of adventure games, Sierra and LucasArts, had languages that were created specifically to help with making their games.

In 3D games, after the groundbreaking success of Doom, the game Hexen added a scripting language to first-person 3D games. Later on, the Quake engine used a variant of C, QuakeC, for scripting purposes. The UnrealScript language, developed for the first Unreal in 1998, distinguished itself for allowing the script programmer to extends classes that were defined in native code.

Run-time scripting languages vs. data definition languages

Two types of languages are relevant in the context of this chapter. The first are run-time scripting languages: these languages control the game during runtime. They often have the common control structures of programming languages such as loops or conditionals.

On the other hand, game developers also employ specialized data-definition languages, which are then used in data-driven game engines to control the way the game engine works. One example is a LISP-dialect used at Naughty Dog, which is used to define animations for the animation engine.

Textual languages

Many scripting languages are text-based; however, as we will see in the following section, a growing number are visual.

One of the most common scripting languages used for games is Lua. The language’s development was started in 1993 at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. It has a small language core, other required functionality can be chosen from a multitude of libraries.

Lua has the concepts of events and tags. Events are fired every time something interesting, such as the application of an operator, and function call, … are called. Native code can register for these events and handle them, for example to call a native function. Tags allow Lua to handle events itself. This mechanism allows changing the way Lua behaves itself, so it can for example be adapted to be a domain-specific language with a dedicated syntax.

Lua has been used in the graphical adventure game “Grim Fandango” and was used to handle everything except low-level tasks such as rendering graphics or playing animations.

Python is another popular scripting language. It was started in 1989 by Guido van Rossum as a hobby project. It is said to be easier to learn than other languages. Its disadvantage is that is relies heavily on hash table lookups, and has a large size when added to a game. However, since scripting code often is not used for performance-critical parts of the game, this might not be a large issue. Eve Online’s server architecture is written almost completely in Stackless Python.

A special case of textual languages are natural language programming languages. These languages feature a syntax that strives to be as close to natural language as possible. The Inform 7 language is a prime example for this category. It has been successfully used to create works of interactive fiction. In it, the source code for a game looks more like a text than a program. However, it still has at its core a syntax that needs to be followed, so only a subset of all valid natural language statements are allowed.

An example of Inform 7 can look like this:

The shower is here. It is fixed in place. “Opposite the mirror is the shower, which is closed.” The description of the shower is “When it’s open, you get in it to take a shower. Right now it’s closed, keeping you from using it.”

Instead of opening or entering the shower, say “It is locked down until after the ship makes its jump to hyperspace.” (See http://www.brasslantern.org/writers/howto/i7tutorial-b.html)

Visual scripting languages

So far, we have been looking at languages that can be expressed as text. However, a second category of scripting languages has been gaining more and more traction in the recent years. These languages are expressed visually, most often in the form of diagrams.

However, visual scripting languages have gotten much more attention in recent years. All major game engines (except Kha/Kore ;-) offer a visual scripting language as a core part of their editors or allow adding such a language in the form of a plugin.

For Unity, there are several plugins available, the most commonly known being PlayMaker, uScript and antares Universe. All operate on a similar basis. Unreal Engine 4 comes natively with the Blueprint scripting system. CryEngine has a similar concept of Flowgraphs.

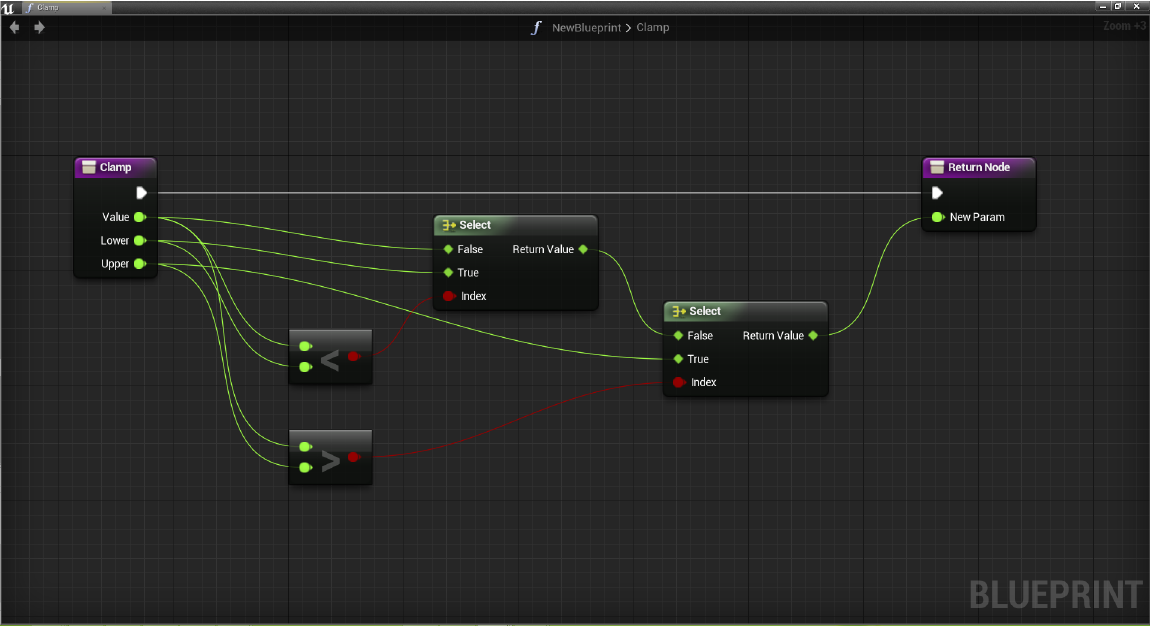

In the image below, you can see the implementation of a clamp function in Unreal’s Blueprint system. The input in the leftmost node are three floats, which are compared to the bounds and either one of the bounds or the value is returned on the far right.

Graph types in visual scripting languages

One of the main factors that influence the usefulness and complexity of visual languages is the type of graph that is valid in the language. In the following, an overview is provided, ranging from simple to complex.

- List of actions In this model, only a sequence of actions is allowed. This very linear approach has the advantage that it is very easy to visualize, actions can be automatically arranged easily and users who are used to very linear writing are not confused by it.

- Sequence with jumps A variation of the first model is used when actions can be jumps to other actions at another point in the sequence. Essentially, this is the equivalent of “goto” statements.

- Trees Allowing for the sequence to branch, it is possible to visualize conditions effectively. This type of graph can still be layouted automatically, making it easier for programmers to retain an overview of their program.

- Series-parallel digraphs In a series-parallel digraph, there is always one source and one drain node. Essentially, this is equivalent to a tree in which we attach the drain node to each leaf node. This type of graph can still be layouted effectively, and has the advantage that branches can be joined again. For example, in a conversation, the character can choose different speech acts in the middle and complete the conversation again with the same sequence for all branches.

- Graph An unrestricted graph is the solution most often used. Here, programmers draw nodes onto a canvas and freely connect them with each other.

Data in visual languages

Two main ways of handling data are common on visual languages for games. The first is to implicitly handle data, i.e. not visualizing it in the graph. In this case, the conditions between nodes indicate state changes, and data is accessed or changed by the actions themselves, for example using a blackboard architecture.

The contrasting approach is to explicitly handle data in the graph. In this model, nodes have output sockets at which data leaves the node, and input sockets where the node can be supplied with data. This makes it explicit what data is used in the graph, and also allows the creation of nodes that change the data, e.g. by carrying out a mathematical operation.

Shader languages

Closely related to programming languages are domain-specific visual languages that are related to game development.

For example, several engines provide visual editors for creating visual effects, for controlling procedural content generation engines or for creating shader effects.

The open source 3D modeling application Blender comes with a node-based system which can be used to define how an image is composited from various inputs and which also allows defining how content is generated.

As we have seen in the lecture on Procedural Content Generation, Substance Designer is a tool for creating textures along with normal maps and other information. The generation process and its stages are visualized and edited using a node-based approach, in which each node is either an input, a function that works on its input, or a terminal node, which creates an output.

Unreal Engine uses a node-based system for building shaders.

In each of these cases, we have the advantages of scripting languages and visual languages applied to the specific field these tools work in:

- They are designer-friendly, allowing artists to create for example a shader that will work well with their created art in the game or to streamline their art production process.

- They allow users to see intermediate results. For example, in Substance Designer, you can click on intermediate nodes and see what their result looks like. In this way, the generation process can be easily debugged visually.

- They allow defining functions and stages much more easily than text-based languages. For example, consider how you would write a shader. Let’s say you have a shader that consists of several stages, and you want to have control which stage is run on which platform. In a text-based shader, you could make a case distinction at runtime - this would not be performant in many cases. You could keep several versions of the shader - at the cost of having less overview. In a visual language, you could define each stage as a new node, and compose each shader as a specific configuration of these nodes. If you made a change to one stage, this would ripple through to the other versions.

Game Engine integration

In order to integrate a scripting language, several options, depending on the programming language and the implementation of the game engine itself, are available.

- Scripted callbacks In this variant, most of the behaviour of the game is hard-coded. At certain points, script functions are called, and can change the game state.

- Scripted event handlers As a special case of callbacks, scripts can be called whenever a certain type of event is registered in the game engine.

- Extending game object types Languages such as UnrealScript allow the native classes of the game engine to be extended. In this way, the scripted functions can be called via composition or aggregation.

- Scripted components/properties Game engines which utilize components to build up their game object types can make used of scripted components. Here, a component can be either supplied by the native programming language or by the scripting language.

- Script-driven engine systems In this architecture, whole sub-systems of the game engine are realized in a scripting language. For example, the game objects might be realized in the scripting language instead of the native language.

- Script-driven games* Finally, in some cases, the game is mainly written in a scripting language, with the game engine acting more as a library for accessing low-level functionality or implementing performance-critical code.